An elevation gain of 3,000 feet in a matter of four miles, surely enough to dissuade all but the most avid of hikers: This is the Harding Icefield Trail.

I set out due North, after a brief morning jaunt around the Seward waterfront. What awaited me outside of city limits was a spectacle the likes of which I'd never had the opportunity to lay eyes upon, a glacier. In fact, my first sighting was set to be the famous Exit Glacier, a crown jewel, albeit a receding one, of Kenai Fjords National Park.

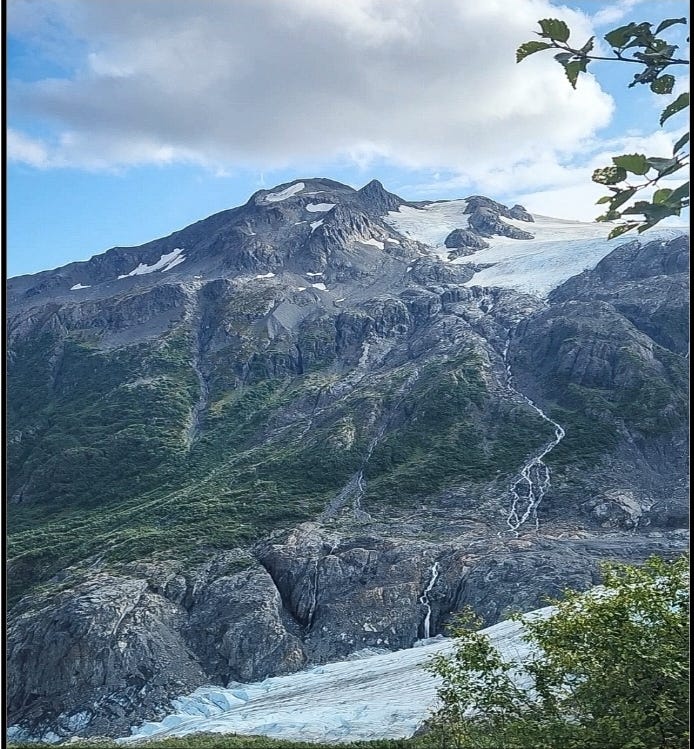

A drive up Exit Glacier road promised entrance to this land bespectacled with the finest graces and likewise bestowed with considerable icy wildness in the form of a valley choked with the remnants of a lost age, the current birthplace of glaciers exposed in every conceivable direction, carving the land into its finest evolution as assuredly as any other transformation in this ever-changing world of ours.

I have heard the process described as "world building," and have yet to find a more suitable description. Concurrently, the question of how the warming climate will impact the literal shape of the future in light of less habitable conditions for permanent ice structures and formations will be fascinating to observe as it unfolds, if not equally damning and distressful.

I parked the car in a lot now teeming with other sightseers. Everyone must get their chance to see or even touch a real life mound of frozen blue solidity, a glacier’s rock-grinding prowess well known and apt to inspire a fair degree of awe in most.

My aim here consisted of positioning myself as close to the glacier as possible, while at the same time affording a bird's-eye view of the Harding Icefield, in the least I desired to see what a vast landscape of ice acting in the way of frozen cement appeared as in reality.

A quick sweep of the car revealed little in the way of potential bear attractant. I was off - into the realm of the forested high country entrusted with Alaska's highest endowment of beauty, stored away from the likely masses.

A relatively short hike past interpretive signs, the shuttered visitor center with a crowd, part waiting for the restrooms and the others milling about until their turn to refill water bottles and flasks commenced, and the semi-adventurous few walking the less intensive beginning of the trail, and suddenly I was immersed in mostly silence.

Meanwhile, the path began to cut through dense thickets of spruce, aspen, and the like, wandering over slight expanses and outcroppings of pale gray shale exposed to limited daylight through the restless action of innumerable watercourses of all sizes and capacities.

I hobble delicately over stream after gurgling steam, pausing to inspect the most unique of the bunch, not haphazardly sending a nearby rock or two to a predestined resting place somewhere downwards.

A casual reminder, a pang of acquaintance, flits into my conscious awareness, charging memories of similar waterborne obstacles traversed in the Angeles National Forest, Icehouse Canyon to be exact in this reminiscence. Far from a one to one comparison, yet a worthwhile one at that.

There is simply water present here in such an abundance as would enthrall, in the most shocking of convivialities, even the most optimistic Californian, were the settings abruptly switched or otherwise made justly similar.

Below, the outwash plain of Exit Creek sneaks tendrils of newborn freshwater on a course well worn in the picturesque valley. The last of this year's Fireweed crop lifts pinkish-purple blooms furtively into the receding summer sky. It is remarkable how profusely these plants grow, and in conditions marked by wretched disturbance that would make others despair.

There are Salmonberries too, just in season, ripe and globular red collections forming at the base of alien-like buds. Had I known at the time that these fruits were edible, I would have graciously partaken of their offering. At this point, I had no cell service from which to obtain the necessary edibility information, and therefore declined with a purposeful thought directed towards those unfortunate souls in lore who perished after consuming what turned out to be less than agreeable to the human body and its needs.

The showy, similarly blood-red berries of Sitka Mountain-Ash and Red-berried Elder made their presences known in tandem, basking in the clear afternoon light rare in these far northerly latitudes. Ostrich-plume moss and Partridgefoot combed the recesses under the lofty foliage and underfoot, threading together a carpet of effervescent, delicate greenery intending to capture the stray, striking rays of sunlight on occasion making their way through less-stunted growth.

After an hour and a half to two hours' worth of hiking, I reached a viewpoint named Marmot Meadows, at an elevation of 1,572 feet, or 479 meters, above sea level. Here at last I procured a glimpse at the terminus of that great ice sheet beyond the crest of the mountains and further up the trail.

Initial impressions convey an appreciation not measurable by any conventional means, for how is it possible to attach a label, even one of positivity, to a sight as rich in scenic values as this one? It is utterly impossible, impractical even, perhaps irresponsible at worst, to constrain perspective in this way.

Ice meets rock in an unhurried intimacy, a waterfall thunders in muffled reception overhead, rivulets convulse after being replenished by a new wave of melting action. Birds soar in flocks over verdant expanses towards a sea guarded by the pinnacles of newly worn peaks, some with glaciers still caressing their smooth necks above the treeline.

I press on, unwavering in a desire to view, or even set foot upon, the icefield itself. The trail is a rocky labyrinth, making nearly each step a labored affair, an intensive action. Were it not for a clearly defined trajectory, the going would be judged impassable, save for the most fit among us.

The brave remainder of wildflowers remain steadfastly in bloom at this height, defying the prescient advice of their brethren, their predecessors, who have already by now accomplished their sole functionality, and perhaps purpose, to pass on their brilliant enthisiasm to the next generation, rising with the casual flip of a calendar to us, a lifetime to plants irresistibly inclined to the natural flow of seasonality.

I, for one, am grateful for the opportunity to appreciate what I believe is a second purpose of wild blooms: To uniquely add to the explicit beauty of this world through no fault of their own, merely presence. Arriving this late into the season, I regretfully assumed all was lost in terms of hopeful viewing that which makes Alaska famous, among many crucial details, its dizzying array of fleeting coloration, propped up by rich biological diversity, flora in particular.

Prior to reaching the Top of the Cliffs waypoint, offering robust initial views of the Harding Icefield, I approached my mid-afternoon turnaround time. As I digress, it is very easy to get sucked into the notion that turnaround times are not hard deadlines, matter less than they are given credit for, or don't matter at all and ought to be ignored.

I do not subscribe to such twisted logic. It has taken many an instance of becoming lost, a panicking, frantic avoidance of circumstances surely to cause death if the necessary effort to expedite myself out of the situation had not occurred, and stories of others choosing wrong courses of action or otherwise allowing themselves to be placed in harm's way have hardened my perspective over several years of wandering.

In short, I follow my own set rules, dictated by best practices for recreating safely and responsibly: For myself, for others, for the environment in which the rules are dictated. I have made an internal pact to follow grounding rules and principles henceforth established, sticking to a concrete turnaround time being a relevant example within the scope of this experience.

I always advocate for safety, caution, and a healthy skepticism when navigating the outdoors. It is never a good idea to blindly trust the external environment. That is how you die. It is imperative to hone not a blanket distrust of the natural world in this way, nor the opposite extreme, but a truthful balance that honors nuances of the given setting, as well as a frank understanding of one's own abilities to par with obstacles or difficulties, both anticipated and unforeseen.

The backhaul to the trailhead quickly proved to be the more challenging, mildly treacherous, and rewarding half of the trek. The steep terrain allowed for a gliding pace over hard-packed earth, over smooth boulders and rocky surfaces, across streams and rivulets with their teeming, icy flows.

At a juncture with a rendering of the valley once again I stopped abruptly, pausing to take in this impressive viewscape, but also to permit passage of a hiker in a state of fitness apparently far surpassing my own, as he at once glided past in a flurry of tan and olive green, and when he looked back I realized the representative emblem, the telltale patch, the radio, the hat, the unmistakable uniform donned by rangers of the National Park Service.

He offered a remarkably brief acknowledgement, and in a blink or two conjured himself out of sight, lost to the eyes amongst the dense foliage, boulders, and countless blockages further down the trail.

After paying due attention to an outcropping of ferns near a seep, skipping over watercourses, leaning closer to attempt to identify foreign mosses, and absorbing every detail of hallowed surroundings, I arrived at length back to where I started, on level ground, passing benches, informational displays, and tourists searching for a sense of direction, of themselves, whether they realized it or not.

I can hope that this place remains a treasure as it stands, with threats of excessive visitation, climate change, and altered habitats looking to morph the natural order of ecological functionality.

As of now, I package that hopefulness with an appropriate expression of limitless gratitude, the level of awe that inspired formal protection years ago, and a boundless curiosity to learn more for the purpose of establishing a higher level of harmony with the landscape, then sharing valuable insights with whomever I can.

In essence, we can all stand to be better stewards of our public lands, not just for our own benefit as human beings, but for the collective benefit of every living being intricately tied to the land, inhabitants and visitors alike in unison.